Around our visit to the Alpabzug, unsurprisingly, we also took an interest in, you guessed it, cheese. And that brought us to the small town of Stein. On the edge of this village in the canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden, there is a complex of two buildings that do a magnificent job in telling the story of local agriculture. There is a museum which displays beautiful folk are with lots of cows and flowers, a live person in a shed who makes cheese with traditional equipment that you can buy in the gift shop (yes, you heard right: go to a museum to buy cheese) and a host of other bits and pieces of local history. It’s a modern, light building with plenty of room for all the art and artefacts. Next door is the Schaukäserei, a place that explains the history and the art of cheesemaking in the region, wrapped around a large cheesemaking facility.

One of the best exhibits is a film that shows an interview with an old Senn, who tells the story of his growing up with a dozen siblings on a farm where the diet consisted largely of bread and dairy products: butter, whey, cheese, milk. Sennen spend their days in summer herding cows, milking them and either transporting the milk down the mountain or turning it into cheese right there in a shed in the meadows. Even today these men and women work in the open with most of their interactions limited to their bovine charges. The old man’s eyes light up when he speaks about the cows, how he likes talking to them and rubbing their heads.

He goes on to explain how the cheese he was used to was normally low-fat: the cream would be scooped off the milk and turned into butter that could be sold at higher prices, and almost immediately: butter provided cash-flow. In the town of Appenzell they still sell this cheese, and call it Rässchäs, sharp cheese. And that, my cheese friends, is not an understatement. This cheese combines and surpasses the sharp saltiness of really old Dutch cheese with the potent stink of a Munster. In fact, a quick scientific survey of everyone in the family irrefutably concluded that it is was worse than any cheese I had ever dared to bring into the home. Räss in flavor and smell, indeed. It is the kind of cheese that will put hair on your chest – I thought it was impressive in the best possible way.

The unusual cheese choices in this part of Switzerland don’t end there. I picked up a few slices of Schlipferkäse at a cheese shop that seems to specialize in unusual cheeses. It came with an interesting recipe: soak a slice or two overnight in lukewarm water (cover it up, but do not refrigerate). The next morning, pour off the water, cover the cheese with some cream, add salt, pepper and cumin as you like, and eat it for breakfast with some boiled potatoes with the skin still on – Gschwellti, as the Swiss call them. Yup – true recipe. I tried it without the Gschwellti and it’s quite pleasant, although I doubt I would often want to go through the trouble. To me some hard cheese with a slicer is easier and less work.

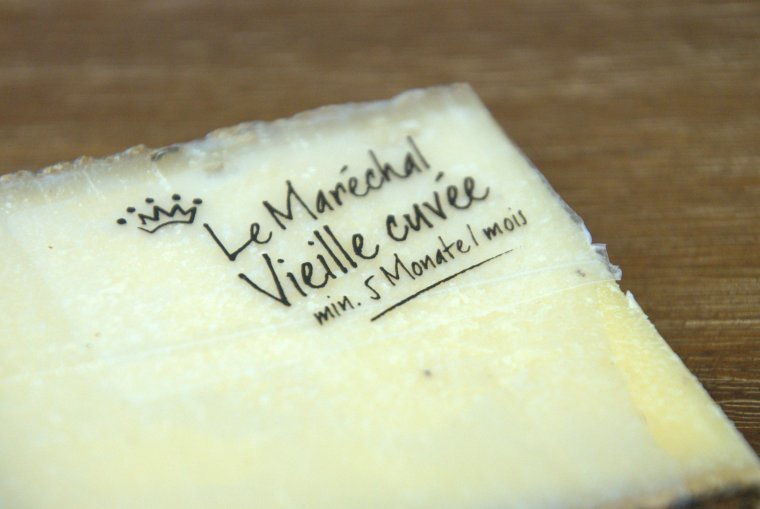

Finally, I got a piece of Suurchäs, sour cheese. This cheese is produced in the neighboring district of Toggenburg, the modern incarnation of a medieval county with the same name. it is made of skimmed milk and therefore has a lot of protein, without much fat. It is white, with a fresh and somewhat sour taste, and as it gets older, a shiny layer develops on the surface that looks a bit like bacon, and is hence called ‘speck’. All three of these cheeses are rather acquired tastes, but not so much the fourth cheese I brought home from Appenzell. It came from the neighboring community of Urnäsch, where the family farms work together in a cooperative that markets several local cheeses very professionally. One of them is made with milk only from cows that have horns – there is some evidence that the milk of these animals tastes a bit different. I got some Urnäscher Brauchtumskäse, heritage cheese, if you will. This one comes in three different ages and mine had ripened for somewhere between 6 and 8 months. It is not a miracle that it won a Super Gold award at the World Cheese Awards a few years ago, because it is salty, creamy, and chockful of flavor. And yes, to make it a nice round number, we did purchase a piece of Appenzeller Edel-Würzig, marketed as superior spicy on the Appenzeller website. The secretive men (and, recently, a young boy) that appear on large billboards throughout Switzerland tell you through their silence that you’ll never know the exact composition of the herb bouquet that finds it’s way into the cheese. And if you would, they may just decide to never let you leave, to protect the trade secret. Things could be worse.

A nice, interesting chäs from Switzerland was my cheese of the week this time, number 42.

A nice, interesting chäs from Switzerland was my cheese of the week this time, number 42.